Not Ready: What Independence Could Truly Mean, but doesn’t

Fifty years ago, there was a debate raging in The Bahamas. It was your pretty typical Bahamian debate. One group of Bahamians were agitating for full self-determination, in this case political independence from Great Britain. The other group of Bahamians were arguing that we were “not ready” to govern ourselves.

I was nine years old at the time. That didn’t make me old enough to really understand what was going on, but I could feel the passion in those around me, and I appreciated it was kind of a big deal. On the one side were people on my father’s side of the family, who, along with my mother and my uncle, were super-proud and super-nationalist. They argued that the only way to be ready was to take the plunge. On the other side were people on my mother’s side of the family, who suggested that we needed to learn how to govern ourselves before we could govern ourselves. That independence so early was foolhardy and we would make a mess of things. We weren’t ready.

This is a debate that I have heard again and again and again over the course of my life. No matter what the topic, it seems, no matter how we look at it, no matter how long it has been since we took the plunge and headed for independence, we are still making the same old argument. Fifty years on, there are still groups of Bahamians who take the stand that “we” are “not ready” to do … whatever it is we know we ought to do.

Right now, what’s most pressing for me personally, as an Associate Professor at the University of The Bahamas, the only Bahamian university in the entire world, the same debate has had a major impact.

What, it seems, “we” are “not ready” to do, fifty years after Independence, is lead our own university.

Bahamians are not qualified enough, experienced enough, exposed enough, whatever enough, to lead a Bahamian university. Apparently knowing something about one’s country is, well, not enough.

These days, we seem governed by this maxim: the first choice is foreign, the second choice a Bahamian who lives in foreign, the third choice a Bahamian who stays here.

It wasn’t always so. In 1974, when the College was founded, we sought to be led by the best among us.

But times, it seems, have changed.

Almost a year ago, after an international call for applicants to serve as the next President of the University of The Bahamas, the inaugural UB Board of Trustees and its search committee sat down to deliberate on who would be the best choice. By summer they had narrowed it down. After having screened over 70 applicants (so I’m told), several of them Bahamians with creditable experience (one of them the former Provost of the University of The Bahamas), the shortlist was released, as follows:

Sir Anthony Seldon, retired Vice-Chancellor of Buckingham University

Dr. Erik Rolland, Dean of Business Administration at California Polytechnic & State University

Dr. Ian Strachan, President of the Northern Bahamas Campus of the University of The Bahamas

Three men.

Two white men.

Two non-Bahamian men.

For the Bahamas’ national university. 47 years after its establishment.

In the part of the twenty-first century when Me Too and Black Lives Matter are making other lilywhite, Eurocentric universities around the world rethink the people they put in charge, we here in The Bahamas seemed to think that a shortlist like this was acceptable.

But wait, I said to myself: at least they have Ian Strachan on this list. After all, who could be better suited for the job? He’s been being groomed for it at least since 2012. He was elevated to VP status seven years ago. He was mentored directly by a former UB president. He was promoted to Vice-President of the Northern Bahamas campus, presumably to continue grooming him for the top job of the whole university—and in that capacity built that campus even after its destruction by Hurriane Dorian. And round about the time he submitted his application for the presidency, he was elevated to President of the Northern Bahamas Campus. It’s a no-brainer, right? This man, this graduate of the Bahamian public school system and this product of the College, is going to be our first Independence-era, homegrown, home-educated President. What better message can any governing body send to the nation they are representing than that?

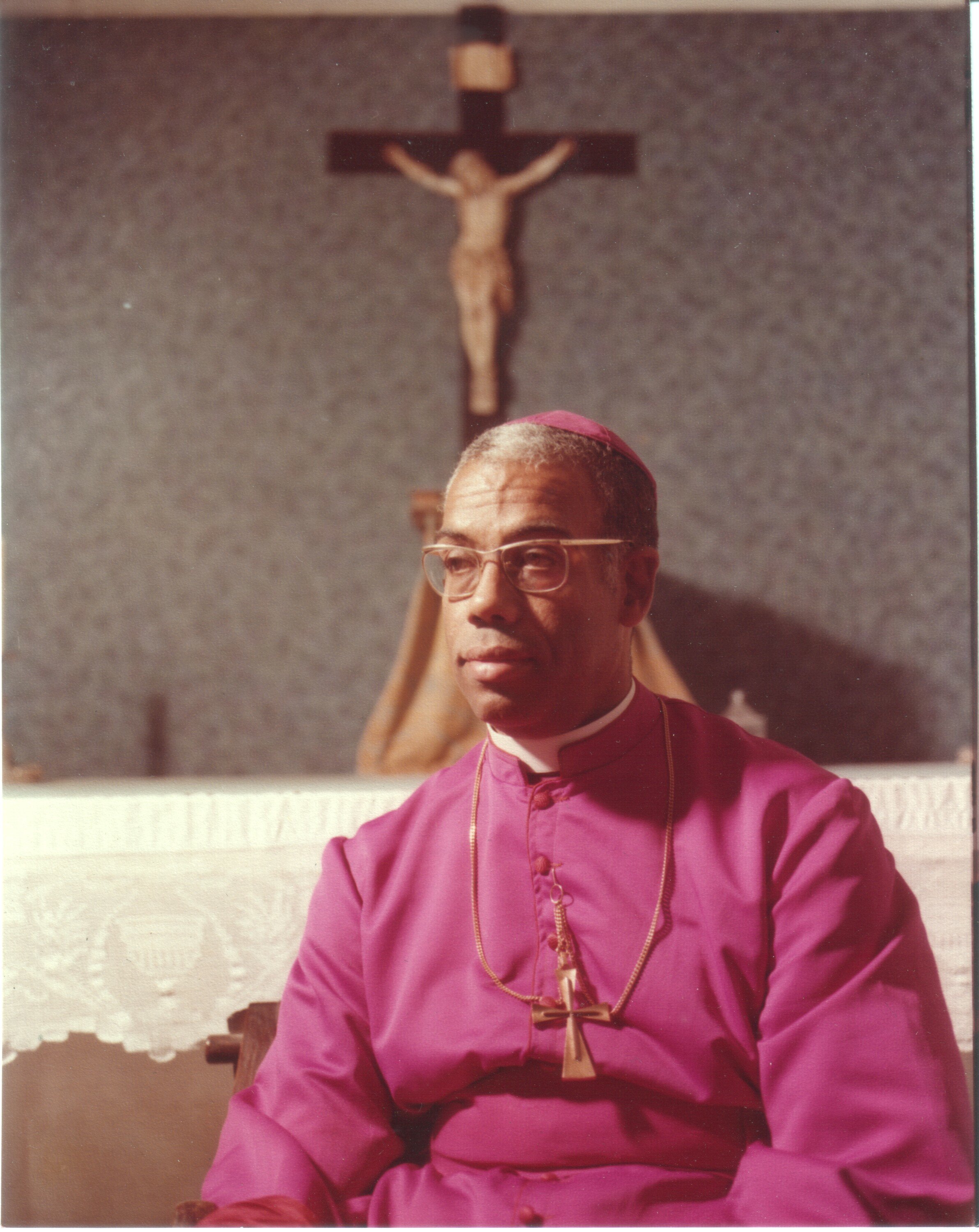

Dr. Ian Strachan, President of UB North Campus

Not so fast, Nicolette.

Apparently, plenty of people—led by the Board of Trustees of the University of The Bahamas, but followed, it seems, by many others—think that retired vice-chancellors of private British universities or serving deans of state polytechnics are as qualified to lead The Bahamas’ only national university as a man who grew up here, was educated here, gained international experience in stellar HBCUs and eastern seaboard colleges (Ivy Leagues among them), returned here, wrote his dissertation about here, published his books about here, built critical political awareness through theatre and discussions here, is raising his children here, is planning to send those children to the very university he wants to head—here.

More qualified, in fact, because the job has been offered to the Dean.

Not the Bahamian President.

The best is foreign.

Second best is Bahamian who lives in foreign.

Third best is Bahamian who stays here.

But maybe there’s more.

Maybe that word “foreign” is code. We live in a world, after all, that Europe made. We live in a world that was shaped in such a way to build a pyramid of worth and value that had Europe at the top and Africa at the bottom, and if we’re not careful, we will continue to build that pyramid forever.

Because I ask myself this. What does a dean of business administration of a polytechnic university have that makes him more suitable to lead a national university in a postcolonial nation than a president who already works there?

Could the answer possibly lie in the one attribute that Ian Gregory Strachan does not have? A white skin?

Is that what makes a dean more suitable for a growing, challenged, complicated, difficult, postcolonial black national university in a growing, challenged, complicated, difficult, postcolonial black nation than a president?

Does whiteness really still trump local expertise, commitment and vision?

Does it drown out the achievements of the man who has given his career to his nation and his institution, who has raised a drowned campus from its sediment?

If you white, you all right.

If you brown, stick around.

If you black, hang back.

Fifty years on, we are, apparently, still not ready.

But I might be wrong. Judge for yourselves. I’m giving the last word to the man who was and remains my pick to lead the University of The Bahamas and prepare the next generation of Bahamians for the next fifty years of Independence. You listen. I might be wrong. You tell me.