Whiteness, Racism & Reparation

On Friday, I shared a post that popped up in my Facebook feed with the one-word comment: “Discuss”.

This was the article: How To Tell If A White Person Is Racist With One Simple Question. The question in question is “Should our nation pay reparations to black people for the enslavement, mistreatment and economic exploitation of them and their ancestors over the past four hundred years?” The article is almost eighteen months old; if it were a human child, it’d be walking. I don’t know why it popped up in my feed on Friday past. One doesn’t ask these questions of Facebook’s algorithms (though perhaps one should). And it’s not a stand-alone. It’s part of a three-part meditation written back when the Trumpworld was still young enough to perhaps seem benign, if you squinted hard enough and had one glass eye. The other entries are these: A Reasonable Reparation and Paying My Reparations, both of which should also be read to inform the discussion. And it’s inspired by a different kind of essay, the kind that gets published in The Atlantic. The author of that one was Ta-Nehisi Coates.

What was interesting to me, and part of why I’m writing this entry (which may be a beginning of something perhaps), is that people took the one word to heart. Discussion was had—and, one hopes, is ongoing.

Photo by Christian Newman on Unsplash

I’ll see if I can attempt to summarize the breadth of the discussion so far. And I’m going to try and contextualize the discussion as far as I can, because context adds an interesting filter.

There’s the observation that the article is oversimplistic, and that opposition to reparations does not mean that one is racist. This was an observation that was offered, and supported, by a number of people of all backgrounds (which is code, as far as this blog entry is concerned, for “races” as well gender, geographical placement, economic status, etc)

There’s the complete affirmation and reinforcement of the position offered in the article. This, too, was a position taken by people of most backgrounds (remember the code outlined above), but more so by people of African descent or by women of non-African descent

There’s the observation that the article is related specifically to the United States of America (which it is, because of course the world begins and ends at the borders of the USA)—with the implication that the argument might be different if it is applied in different post-slave societies with different histories. This was proposed by one or two people only

There’s the argument that reparations are irrelevant or impossible (not entirely sure which) because slavery is over and modern-day people who did not directly benefit from it should not have to pay for the injustices of their (or, perhaps preferably, other people’s) ancestors. This argument was not so evenly offered by people of all backgrounds; while there was some diversity, this argument tended to be put forth by men of whole or part European ancestry

There’s the argument that despite adverse circumstances in the past, despite a history of disadvantage, progress has been made either personally or collectively, and that progress eradicates or at least mitigates the damage done in the past. This argument tended to be advanced by men of mixed or non-African backgrounds

There’s the argument that the lines are not so easily drawn outside the USA, which defined “race” with a mathematical precision that ensured the continued oppression of many people who would not be recognized as “black”—unlike, say, the Caribbean or other parts of the Americas, where society endured and made room for more mixing, resulting in variants of pigmentation rather than monoliths of race. This argument was advanced most commonly by non-American women

There’s the argument that paying money for past wrongs is not a valid mode of compensation, because money is easily wasted. This was advanced by people of diverse backgrounds, most of them male

There’s the argument that the discussion does not need to be had, and in fact can be divisive and potentially negative. This was advanced by male individuals of mixed descent

There’s the argument that reparation is not about money, but about principle; money may be a fitting symbol, but it is not the point. This was advanced mostly by women.

One of the commenters asked me to write an article in a similar vein. Not sure I can do it, or that I haven’t already done it. But what I can do is begin a meditation inspired by the post and the ensuing discussion.

First things first: where I myself stand.

I shared the article because it was provocative, but also because I don’t buy the simple equation of anti-reparations = racist white person. In this regard I stand with those who raised the (obvious) question of what to do with/where to place those people who are not white and who don’t believe in reparations. I do, however, support the idea of reparations. No. That’s putting it mildly. I am utterly convinced that reparations for the institution of slavery must be paid. Moreover, I believe that they will be paid, eventually; if they are not, it is because the institution of democracy has failed, the concept of the human has died, and the ideas of human rights and humanity have become obsolete.

Boom.

At the same time, I would also propose that the argument against reparations is itself racist. But it doesn’t follow that people who make the argument must be racist.

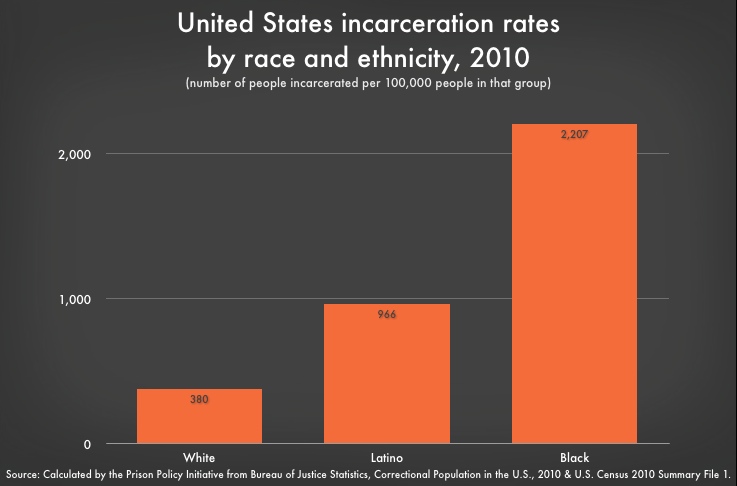

Aha, you say. A contradiction, you say. Absolutely. It is contradictory, but it is nevertheless very possibly true. It’s true because we still inhabit a world that was only made possible by half a millennium of the forced labour of millions of people whose humanity was stripped from them and their offspring in perpetuity, and whose humanity is only being returned to them (us) piece by bitter piece as our voices confront the institution and the world that it made and dismantle it bit by bit. Our entire reality is racist, and that racism shapes us all. It dwells in our deepest unconsciousnesses, no matter what our outward appearance might be. It lurks in the easy associations we all make, again and again, as easily as breathing: associations that link blackness with savagery, sexual appetite, violence, idiocy, brutality, dishonesty, laziness, criminality, shiftlessness, dirt, vagrancy, ugliness and filth, associations that link whiteness with purity, civility, intelligence, justice, law, industry, thrift, cleanliness, beauty and right. It lurks in our complete obliviousness to the brutality on which the institution of slavery depended. It lurks in our inability to recognize the perpetuation of that brutality in the daily life of the twenty-first century, brutality that lives on for all of us in expressions as apparently benign as “good hair” or as destructive as the reference to people who may be young and black as different sorts of animals (heifers, dogs, bitches, bucks, monkeys, cats, etc).

Reparations are necessary to expose these associations. They must be monetary because the crime was, in its origin, monetary. The current issue is barely how that money should be spent; the current issue is that to repair the great wrong done to the entire human race by the institution of chattel slavery (not just one group within it) it must be paid. That is the first level of the discussion. The rest of the discussion—the place where the idea of reparations opens up doors to creativity and innovation—is still to come.

But this is where I stand. As long as we conceive of the discussion as one which highlights racism, we miss the point. The point is that the kidnapping, sale, and enslavement of Africans, together with the entire systematic and ongoing dehumanization of the very idea of Africanness that was necessary to prop up the institution of slavery in an age of enlightenment, is a crime that continues into the present day. Think of James Byrd being dragged behind that truck. Think of the children forced to live in filth and captivity at the US border. Think of all the different mundane acts of violence, great and small, we accept as normal in the Caribbean. Think of the currency of these ideas: that the ripping of people from their homelands and the stripping of their identities from them is something that can be past, buried and done with, or that the robbing of land from the people who inhabited it and their eradication from public consciousness is simply the way the world is.

These are the parameters of that crime, and they continue. They replicate. They are supported. The political and economic elements of that crime may have passed away, perhaps. But the systems of dehumanization remain in place, and remain largely intact.

And. That crime is enacted not only on the descendants of the kidnapped. What we fail to see in the discussion we’ve been having so far is that the crime is perpetuated just as much on the kidnappers as well. In order to dehumanize the “other”, the people who designed and perpetuated the institution of slavery had to dehumanize themselves. They had to transform themselves into torturers, rapists and murderers, and they had to do so systematically and legally. They had to leave no room for the kind of doubt that might cause the system to fail, and so they built societies that legitimized and rationalized those actions.

It is that which must be repaired. This is a reparation that is far larger than the United States of America (which, after all is not the world). It is a reparation that has to happen to begin to rebuild us all.