CRB • No. 30 • November 2013

One of my favourite online magazines -- if not my very favourite -- is back up and running!Go, Nicholas!!CRB • No. 30 • November 2013.

One of my favourite online magazines -- if not my very favourite -- is back up and running!Go, Nicholas!!CRB • No. 30 • November 2013.

This is not the post that I would have liked to write in the days after the close of The Legend of Sammie Swain, but it has to be done. We received so much support from our audiences and so many congratulations from the public at large for the revival of my father's folk opera that I wish I could say that we have been able to pay our bills, but at this point in time I cannot.In another post, I explained the cost of theatre to those who do not know better. I think I may have to refer people to that post again, because I am sure that people have looked at the apparent success of this year's Shakespeare in Paradise festival from the outside, seen the sold out houses and the turned away crowds, and come to the conclusion that we are rolling in money.Far from it! I'm not going to go into details, but the simple formula is this.Our festival as a whole cost us over $110,000 to mount. Sammie Swain accounted for about $75,000 of that. We estimated over $100,000 for the show, but we cut our costs to the bone and delivered it for 75% of the projection.Our festival as a whole had a total of 5,870 seats to sell. Given our $110,000 cost, that sets seat prices at $18.75 at FULL OCCUPANCY if we were to break even. However, even with Sammie Swain, we did not operate at full occupancy -- only the last four performances sold out. Sammie Swain had about 90% occupancy, and the festival as a whole had 75% occupancy overall. This made it our most successful festival ever, but it means that brings our seat prices to $24.98 a head for us to break even.But we didn't sell all our seats at $25.

This is not the post that I would have liked to write in the days after the close of The Legend of Sammie Swain, but it has to be done. We received so much support from our audiences and so many congratulations from the public at large for the revival of my father's folk opera that I wish I could say that we have been able to pay our bills, but at this point in time I cannot.In another post, I explained the cost of theatre to those who do not know better. I think I may have to refer people to that post again, because I am sure that people have looked at the apparent success of this year's Shakespeare in Paradise festival from the outside, seen the sold out houses and the turned away crowds, and come to the conclusion that we are rolling in money.Far from it! I'm not going to go into details, but the simple formula is this.Our festival as a whole cost us over $110,000 to mount. Sammie Swain accounted for about $75,000 of that. We estimated over $100,000 for the show, but we cut our costs to the bone and delivered it for 75% of the projection.Our festival as a whole had a total of 5,870 seats to sell. Given our $110,000 cost, that sets seat prices at $18.75 at FULL OCCUPANCY if we were to break even. However, even with Sammie Swain, we did not operate at full occupancy -- only the last four performances sold out. Sammie Swain had about 90% occupancy, and the festival as a whole had 75% occupancy overall. This made it our most successful festival ever, but it means that brings our seat prices to $24.98 a head for us to break even.But we didn't sell all our seats at $25.

Our ACTUAL average ticket revenue, all told, comes to about $14 a head, which this year was a loss of about $11 a seat. We are still working out our actual take, but we know we had audiences of over 3000 people this year. 3000 x $14 = something over $42,000.We made about $30,000 from sponsorships, donations and ads. Some $5,000 of that money, which is 1/6 of the total sponsorship, came from crowdfunding. Most of the rest came from small and medium companies (here I am not including the invaluable in-kind sponsorship that we continue to get from companies like Cable Bahamas, Starbucks/John Bull and Marcos/Wendy's, which assist us with our advertising and allow us to treat our performers like people by providing them with some very basic refreshments even though we can't pay them salaries). A little came from more substantial companies who understood what we are trying to build, but nowhere as much as you might think.That brings us to a total of about $75,000, give or take, in revenues, for a shortfall this year of some $35,000.How did we meet the shortfall?We always try to pre-sell our festival by seeking corporate sponsors. We really worked our butts off this year in this regard, and if we had got all of the sponsorship that we asked for, we would have been able to raise in the vicinity of a quarter of a million dollars. Even a quarter of what we asked for would have netted us enough to cover our costs. But we raised only one tenth of what we asked. So far, the Bahamian government and the Bahamian corporate community have not shown that they understand the value in investing in something intangible that is nevertheless part of our culture. They don't know why we can't cover our costs by selling enough tickets.But they don't know what we know: that because there is so little support for the arts in The Bahamas we cannot sell seats at what it costs us to produce our shows. If we were to sell seats at what it costs us to put on the Shakespeare in Paradise festival without paying our performers, each seat would cost you, the public, $40 or more. If we were to pay our performers, rack that up to $75 a head. And who can afford that?We sell our seats at what the public is willing and able to pay—$25 for a full price ticket. But we go beyond that because we believe that art is not only important, it is necessary to make whole human beings. So we perform as many matinees for students as performances for the general public. And we sell student tickets at between $10 and $15 a head.In most countries and cities, governments, corporations and private individuals help artists produce great works that define their populations by subsidizing the cost that it takes to produce that art.In most countries and cities, great works of art are understood to be investments in national patrimony, identity. They are collected and guarded as closely as all other kinds of treasure. Most nations understand that it is great art that will survive, that will tell the story of the civilizations that existed, and nothing else at all. In other words, it's only our art that will remain when our Bahama Islands sink below the rising sea.Here, we've so far been fighting an uphill battle to convince our governments and corporate citizens of the value of what we do.Since Sammie Swain opened on October 4th, 2013, we have received several promises from government members both to address the shortfall and to remount the production. Nothing concrete so far has come out of them, so we will believe those promises as soon as we bank the cheques. (All Bahamians should know what government promises about culture can amount to--CARIFESTA, anyone?). To date, despite those promises of support, government investment in this year's festival, including Sammie Swain, was half of what it has been in other years.Thankfully, after this month's production of The Legend of Sammie Swain at Shakespeare in Paradise, when my brother announced on the closing night--as he had on the opening--that we are facing a shortfall that threatens the future of Shakespeare in Paradise, some individual members of our community took it upon themselves to start a campaign privately that will help us meet that shortfall. I don't have permission to say who, so I will not name names, but to them I say a great big THANK YOU. They know who they are.To everyone else, I say: this is the state of our culture, Bahamians. We all bear responsibility for it, so let us shoulder that responsibility together. And now, if we believe that we are important, let's do something to make it change.

People have been asking, as they do, what makes it cost so much to put on a theatre festival. It's a question we come up against a lot, whether it's asked in a straightforward fashion or whether it's behind some other question or assumption, such as the one I was asked outright last year: "Why can't you afford to pay the actors just a little bit--say $50 a day--for their participation?"

Part of the issue may be that these people see that we're selling tickets for our productions and make the assumption that the revenue we earn from that not only covers our costs but makes its way into our pockets as well....

Hold on. I'll be right back. I'm laughing too hard to see the screen just now....

OK, I'm back. And my laughter has been replaced with perplexity. After all, we all see the world from our own perspective. Maybe they--people, you, whomever--think that theatre is just about getting up on some empty stage somewhere and throwing out a few lines. How much can that cost anyway? And to top it all off, you're selling tickets! Pure profit! Why can't you share a little?

I can only speak for myself here, but I'll try and break it down.

When Ringplay Productions, our theatre company, or Shakespeare in Paradise, our theatre festival, prepares to put on a play, the first thing we do is choose a play. We like to do so based on some agreed-upon criteria. For Shakespeare in Paradise, it's either a Shakespeare play we haven't yet done, or it's a piece that we believe will speak to our audiences. Shakespeare in Paradise is dedicated to the production, preservation and celebration of Bahamian, Caribbean, African-American and African diaspora works because there aren't many theatre festivals out there that have a similar focus, and because the vast majority of our theatre scene in Nassau is introspective, focussed on current affairs and local issues. We seek to fill a gap.

So, back to basics: we choose the play.

Most times it's written by someone else. Many of those times, then, we have to pay for it. That's right! Plays are not free! Playwrights get paid royalties! and so that's the first cost we have to consider. It's a relatively minor cost, and is often calculated based on type of production (professional/community/amateur), but normal royalty payments total about $500-$600 per production.

So off the top: $500-$600 in cost.

Next we have to cast the play. To do that we like to hold auditions. We don't have to, as we could just pick people to be in the play from the people we know, but what would be the fun in that? Or, to look at it another way, that would not be in keeping with our desire to offer experience and exposure to a wide variety of people, so we have to hold auditions.

For that we need:

a space big enough to hold the people who come to audition

copies of the audition pieces

registration forms OR a tablet or a computer to keep track of the people who came to audition

a camera to take headshots

pens to help people fill things in

So before we get any further: another $500-$600 in cost (sometimes that cost can be shared or waived, depending on our access to the audition space).

Once we pick our cast, we need:

copies of the script

If the script is international, we either need to purchase enough books to give to our cast (that's the strictly legal way) or we need to reproduce it somehow.

In the 20th century this meant taking the script to a copying centre and getting copies made.

In the 21st century this means scanning the script and printing the copies out.

Either way, another $100-$200, depending on the size of the cast.

Then we need to rehearse the play.

For this we need a rehearsal space large enough to enable us to lay out an appropriate set, to encourage actors to project their voices the way God intended people to do before humans invented microphones, and to allow us to block and practice the play.

Rehearsal spaces don't come cheap. If we don't have access to an appropriate space, one of two things will happen. Either our rehearsals will not allow us to work in the physical dimensions that we will find on stage, and the final production will suffer and lose us money in missed ticket sales, or else they will cost us an arm and a leg. No, literally. The best rehearsal spaces come at $300 or $400 A REHEARSAL.

And we have to rehearse at LEAST twice a week (preferably 3-5 times a week for at least 4 weeks). Do the math. Rehearsals will cost us in the vicinity of $600-$1200 a week just for the space alone. This doesn't include the cost of keeping the cast comfortable--i.e. providing at the very least water for them to drink while they are working.

Total for rehearsals: $4800 and up.

So before we even get to the other things that make theatre theatre, we've spent a minimum of:

$500 for the play

$500 for auditions

$100 for scripts

$4800 for rehearsals

for a total $5900 before we can even get near to selling tickets.

So what else do we need?

Well, we need a performance space. A rehearsal space is one thing. It needs to be big enough to hold the cast and to mimic the size of the stage. A performance space is quite another. It has to be big enough for the performers and the audience alike. And it has to be big enough to allow us to generate enough money to help us cover the costs we've already spent.

So let's take the best one out there: the Dundas Centre for the Performing Arts.

The Dundas rents its theatre for a $1000 a performance and up.

The "and up" is often non-negotiable, and can run one to another $300 per performance, so the Dundas can cost you $1300 per performance.

Sounds like a lot (and is) but here's the advantage: for that $1300 you get the basics: 330-seat theatre, parking, lights, sound, security, dressing room, backstage, performers' entrance, performers' bathroom. These things sound simple, but trust me, they're not; NEVER take them for granted if you're doing theatre in this place!

So if you're doing a single performance, your costs have gone up to $7200. And you still haven't started to deal with set, costumes, props, tickets, programmes, or publicity.

So let's do some more math. Let's go back to that selling tickets idea. How much would we have to sell tickets for if we want to cover the costs we have listed so far?

If we sell EVERY SINGLE SEAT in the Dundas, we have to sell tickets at $21.81 to cover these costs.

See where I'm going?

Now let's add in the things that make theatre theatre.

Costumes. These can cost next to nothing if the cast supplies their own clothing, or a couple thousand if we are doing something elaborate, exciting, or unusual. This figure also depends on the size of the cast. A one-person play will cost very little. A large play, like a Shakespeare production or a musical, will cost a lot. Something like 2010's A Midsummer Night's Dream cost in the ballpark of $2000 for costumes, as every cast member had to be clothed in a particular way. Something like 2012's Merchant cost about $200, as the cast all wore street clothes. Let's pick something fairly modest that gives us some room to play with: let's say costumes cost $500.

Props. These, too, can cost next to nothing if borrowed or donated. But some things have to be bought, like fake knives, or anything else needed to create special effects. So let's say another $200.

Sets. These are non-negotiable. Every set costs money. Some cost more than others. Ours cost between $1000 and $6000, so let's pick a mid-point: $3000.

Lighting and sound. If we've invested in the Dundas, these come built in. We will have to pay for lighting and sound operation, but these are included in the cost of $1300. If, on the other hand, we have chosen another space, we are going to have to invest here. An adequate lighting system (something that lets the audience see the cast's faces) can be rented for $2000-$3000, but if we want more (which we rarely get) the cost goes up. So let's pick $2500.

In theatre, microphones shouldn't be necessary for ordinary plays. For musicals, that's a different matter, but in a play, the actor should have developed the ability to project her voice so that the audience can hear her no matter what; so we shouldn't need microphones. But we will probably need sound effects, music and so on. A basic sound system that provides that can be $200-$500. Let's say $250.

So where are we now?

We've just added another $6550 to our $7200.

Our little play is now costing us $13,750, and we haven't got to publicity, programmes or tickets yet; forget paying personnel.

So let's go there now.

Programmes can cost as little as a few hundred for paper, toner, and the printer or photocopier to duplicate them, or as much as $9000 for a full-cover printed deal. Our festival programme costs us a lot to produce and we have never paid less than $5000 for it. When we were doing one-off shows, though, we would run our programme off on a laser printer. That cost us about $150-$200. Tickets, though, need some investment. They are, after all, the things that make you money. Local printers can print tickets at about $400-$1000 these days, depending on how many you need (or you can order them from abroad, which looks cheap but costs something to bring them in -- either customs at the border or a plane ticket to get them here). So let's figure in another $1000 for programmes and tickets combined.

We'll need somewhere to sell the tickets. Some people use ticket outlets, which may donate their services or take a little in commission. Others, like us, use a stationary box office. That costs us money in both rent and personnel. So let's add in another $2000 for the box office.

And finally, publicity! There are all sorts of ways to get the word out there, but know this: the size of your audience depends very much on the quality of your marketing and publicity. Facebook does a lot, but does not do the whole job. The very best form of advertisement is television. For those who can afford it, cross-channel marketing (in the old days it was a commercial on ZNS during the news) is worth the investment -- but what an investment! If you want to sell your tickets, you have to invest several thousand right here. Let's be kind and add another $2000 to our pot.

Total cost of our production with ONE performance only: a cool $18,750.And that's being conservative in our estimate.

What does that come out to if we have to make all our money back on ticket sales then? How much will we have to price our tickets?

Our tickets have just gone up to $56.81 a head WITH FULL OCCUPANCY.

So what if we added in the suggested $50 per person per day? What would our costs be then?

Let's say we're doing a small play, with a few people in the cast. Let's say we have a cast of 4. We also have a director and a stage manager. Let's pay them all the same $50 a day.

Let's say we have a rehearsal period of 6 weeks with 3 rehearsals a week. Let's say that, because there are 4 people in the play, everybody has to be at every rehearsal. And let's say we just have one performance.

The math is 6 x 3 x 6 x 50 = $5400 for the rehearsal period + 6 x 50 for the performance = $300 for a total of $5700.

Our costs have gone up again to $24,450 for a single performance.

Your costs (cost per ticket) have gone up to $74.09 per ticket with FULL OCCUPANCY.

And we never get full occupancy; our most successful productions get about 60% occupancy. So jack the ticket price up again.

Here's how we make it work.

1) we don't pay local actors with cash. Yes, it sucks, but we want to keep doing what we're doing. And we happen to think that there is an exchange of sorts that's going on. There are no theatre schools in Nassau, and no real opportunity for training; the only way actors can hone their skills is by being in productions put on by experienced people and learning on their feet. So Bahamian actors gain experience and training that they don't have to pay for. It's a bad argument, but it's the only one we've got. The alternative is not to do theatre at all.

2) we don't invest all of the above for a single performance only. Yes, our rents go up when we have more performances, but all of the other costs are one-time investments, and they pan out over time. Once upon a time we would make the investment for a ten-night run; these days we find that we need to do at least 4-6 nights to make the investment worthwhile. Here's how that pans out:

Extra Rent = 5 x 1300 = $6,500 plus our base cost of $18,750 for a total of $25,250.

Total seats to sell: 330 x 6 = 1,980

NOW for us to cover our costs, the price per seat at full occupancy becomes a MUCH more manageable $12.75, and the price per seat for the expected 60% occupancy goes back to $21.25. This gives us room to work with less than full occupancy, and gives us the ability to offer bulk sales and discounts.

Maybe you'll get why I was laughing so hard at the top of this article. Pocketing money from theatrical productions is a dream. Covering our costs is the goal. Pure and simple.

That's how it's done.

I'll talk more about this again later, but for now, that's me.

For those of you who may not know, I do theatre in my spare time.

“Spare” may be a misnomer. “Unassigned” may be a better way of putting it. See, I work for a living because I have to; I need that regular income, and most of all I need that health insurance. I’m a college professor. I’m not dissing that. In fact, I happen to think it’s one of the best jobs in the world. It’s the only job in this country that will pay me to do half of what I love to do, which is write and talk, and that will even include that writing and talking when it comes time for promotion, and at the same time also allow me the flexibility and space to do the other half of what I love to do. I bless the people who dreamed up the College of The Bahamas and I bless those people who made it do all these things.

But if I had my druthers, I’d be working in theatre too.

OK, for those of you who do know me, you’re probably saying to yourself: “But she does work in theatre.”

And you’d be right, after a fashion. After all, I am one of the founders of Ringplay Productions, a theatre company that’s been around for the past 13 years, and I’m the founding director of the Shakespeare in Paradise theatre festival.

But nobody pays me to do either. And so I have to do it in spare, or unassigned, or off, time.

Before you ask me, the answer is, yes, I do have a problem with this. I didn’t twenty-five years ago when I started working in Bahamian theatre. In the 1980s, the Bahamas was in its second decade of independence, and had much bigger things to worry about than about providing careers for young artists. I wasn’t raised to pursue such a career, anyway. Even though my father had studied what might well have been the most esoteric thing for a young Bahamian to study at the end of the 1950s—classical piano performance at the Royal Academy of Music, London—my parents brought me up to be employable (my father wasn’t, not in the Bahamas, so a teacher he became). So I did not go to school to study theatre, even though I liked being on stage. I grew up “knowing” that the theatre was something one did for the love of it, despite all odds, and not something one did to make money from. Even though I wanted to write plays I never thought of doing it for a living.

But times change, and people change, and the world changes. In the 1980s we weren’t welcoming five million tourists to the Bahamas and wondering what on earth there was for them to do onshore here. In the 1980s, there were still some things for them to do (although that was the decade when things started to change). There were still cabaret shows in casinos which provided regular jobs for dancers; there were still nightclubs here and there which provided regular jobs for musicians; and there were record stores that bought musicians’ music. Maybe I’m painting too rosy a picture here, but it seems to me that in the 1980s Bahamians liked Bahamian culture.

But we’re not in the 1980s anymore.

It’s the twenty-first century. And if there were every a century in which creativity could flourish, this is it. We live in a time of revolution; publishing and production and filmmaking and composing and making music are in the hands of the creative artists, rather than locked up in boardrooms thousands of miles away in somebody else’s country. And tourism is also changing to reflect this new century. Tourists are not travelling merely for sun, sand and casino winnings. They are looking for unforgettable, unique experiences, and they’re paying premium prices for them. It’s never been a better time to be a creative artist anywhere—except the Bahamas.

Those of you who know me well may remember that ten years ago this October I took on the position of Director of Cultural Affairs for the Bahamas government. Those of you who know me very well may remember what I was like when I took on that job. I am a happier person now, they tell me. I am not so angry all the time. Not so driven. (I would dispute the second, but WTH). I wasn’t always angry and driven. I took on the job believing, as one does, that I could make a difference. I took on the job to help bring back some focus to the Bahamas and to revive a sense of pride in Bahamian culture. It’s important, I believe, to for individuals to have some things done by the collective around them that they can be proud of, but in 2003 too many Bahamians were behaving as though they were ashamed.

I had no idea I was embarking on a wild and crazy ride that would take me through wildernesses and woodlands, across oceans to different continents, to high heights and even lower depths and bring me back right to where I started.

When I worked out that I had gone full circle, or maybe had made a spiral which brought me back to the same point as I’d started from, only maybe further away from where we wanted to be, I left. And started the theatre festival you see me working with today.

Shakespeare in Paradise is now five years old. We have survived by the grace of God and our own hard, hard work. We have grown and done some work that we’re proud of, and because it’s our fifth year and the fortieth anniversary of independence for this country, we’re taking a big, big risk.

And I have no idea where we’ll be by the end of October. In all honesty, it looks like we’ll be tens of thousands of dollars in debt.

The reason?

We dream too damn big.

We’re reviving Sammie Swain, the folk opera that should be my father’s legacy but is dying because it hasn’t been performed for too long.

Why it hasn’t been performed is a long story which I’m proposing to tell here on this blog. There are some villains in this story, and some heroes too, and the villains and the heroes might not be who you think they are. And it’s all part of a much bigger story, which is still being written, but which so far is shaping up to be a tragedy. I want to tell that story too.

So I called this “creating theatre in Nassau, Bahamas” because I had hoped to get to the theatre part of the story. What you have is just the setting and the backstory. Bad storytelling, but live with it.

We’ll get where we’re going if you stay with the ride.

The last couple of weeks have been some of the busiest of the year.

They won't BE the busiest of the year—that time comes in late September/early October for me—but they HAVE been the busiest.

The reason? Well, as soon as the academic year ends for me, the theatrical year begins. Five years ago I was mad enough to imagine and found a Bahamian theatre festival. Shakespeare in Paradise was launched in October 2009 with a handful of people crazy enough to believe in it—and really crazy, because most of them were willing to work for free—and we pulled it off.

This year is our fifth, and it's still going. And we're crazier than ever, because we have determined to revive my father's folk opera, Sammie Swain, in honour of our festival's fifth year, in honour of our country's fortieth anniversary.

These things are crazy because we've added about $100k to our bottom line.

Ah well. We've been here before, more or less. In 2009 we didn't have any money at all. We pulled that festival off through the kindness of many people, and by building bartering relationships that paid off. This year we have a track record and some money, but people are (rightly) not so willing to barter and they're holding their purse strings tighter than ever.

So my vacation has been pretty non-stop grubbing for funds. Translation: my fabulous festival assistant and I have been writing letters, setting up meetings, and looking people in the face, telling them what we need and how much we believe in what we're doing. A lot of little bits of money does the same job as a few big chunks.Money might be slow in coming, but recognition is growing. That's why it's important that we have to stay afloat long enough to make the festival what we know it can and will be. In the meantime, this past Tuesday I was asked to do a photoshoot with Duke Wells to help create a photograph to go along with an interview done by Caribbean Beat Magazine. This is great, because we are getting regional coverage, and from a personal perspective, because I get new profile shots.I like this one:

This is turning out to be a sales pitch and I didn't mean it to be. I just wanted to say that this has been the least like a vacation that I've had in a long time.

And to say keep your eye on our facebook page, and remember the name of Shakespeare in Paradise. It's our fifth year, I've spent my vacations working on it for free for the past five years, and I'm doing it because I believe. I believe in our theatre, I believe in our audiences, and I believe that the Caribbean, and the Bahamas, can produce world-class theatre if we are willing to invest in it.

Watch me.

... and more to the point still standing, and still able to lift my arms (albeit with some effort).

Sperrit rushed this new year in, with gold paint, newspaper fringe, carnival masks and hats. We were: 3 drums, 2 bells, a conch shell, a scraper, and a bicycle horn. We had one lead dancer and two free dancers. One person had never rushed before. I think she had a good time. I had not rushed on Bay Street in 25 years, and hadn't rushed at all since 1994. I did not die.

I'm waiting for photographs of which I approve to post them.

I apologize to all those who tried, I'm told, to catch my eye on Bay Street and in Rawson Square. I was (1) in the zone; and (2) concentrating on making it to Elizabeth without falling out and embarrassing myself. If I rush next year (which depends on whether Sperrit goes out on Boxing Day (NOT rushing) or New Year's (will be rushing) I may be far more sociable.

But hear this: I had me a good ol' time.

Just woke up.Let me backtrack. These holidays are my fiftieth: my fiftieth Christmas, my fiftieth new year's day celebrations. Not that I have much memory of the first of either (I have photographs of both, and a very fleeting series of memories of the former, which I know I spent in Delancy Street in the upstairs apartment that now belongs to my friend Leria McKenzie, and which involves the receipt of what was then a gigantic stuffed panda bear), but the numbers won't let me lie. They are my fiftieth. Just so people don't get confused: I was born in March 1963, which means that the Christmas season of 1963-4 was my first. Next spring I will be fifty, ten years and four months older than our nation. This, I realize, makes me an "elder" these days. I was on Clifford Park with numerous other Bahamians at midnight on July 10, 1973, which makes me part of the independence generation, part of that group who bears responsibility for building, or not building, this nation.This is a long way of saying that this New Year's Day I will be rushing, not reporting, judging, administering or studying Junkanoo. Let me be clear. I will be rushing hardcore scrap, as I have always done. This year, for the second or third time in my life, I will be rushing in newspaper. I have been told, though I do not agree, that to rush scrap is "disrespectful" to "real" groups. It's New Year's Day, however, and this is a parade that I regard as scrap's parade, that I regard as having been hijacked from ordinary people's participation for the love of Junkanoo and of music by the big groups (don't worry, I'm not going to fight about it). I am not rushing to be pretty; I hope at some point in the parade to sound good. And not, by the way, to expire before I make it back to where we started from.So happy new year all. This year will bring changes. New years always do. I wish blessings on all my friends, allies, colleagues and sparring partner. Have a good one.

Just so people don't get confused: I was born in March 1963, which means that the Christmas season of 1963-4 was my first. Next spring I will be fifty, ten years and four months older than our nation. This, I realize, makes me an "elder" these days. I was on Clifford Park with numerous other Bahamians at midnight on July 10, 1973, which makes me part of the independence generation, part of that group who bears responsibility for building, or not building, this nation.This is a long way of saying that this New Year's Day I will be rushing, not reporting, judging, administering or studying Junkanoo. Let me be clear. I will be rushing hardcore scrap, as I have always done. This year, for the second or third time in my life, I will be rushing in newspaper. I have been told, though I do not agree, that to rush scrap is "disrespectful" to "real" groups. It's New Year's Day, however, and this is a parade that I regard as scrap's parade, that I regard as having been hijacked from ordinary people's participation for the love of Junkanoo and of music by the big groups (don't worry, I'm not going to fight about it). I am not rushing to be pretty; I hope at some point in the parade to sound good. And not, by the way, to expire before I make it back to where we started from.So happy new year all. This year will bring changes. New years always do. I wish blessings on all my friends, allies, colleagues and sparring partner. Have a good one.

I have been involved in the performing arts, and specifically in theatre, in The Bahamas for over thirty years. Like many in my generation, my involvement began as I entered high school, continued throughout the 1980s and 1990s and blossomed in the 21st century. For all of that time, my mentors were great Bahamians who, sometimes at considerable personal sacrifice, had committed themselves not only to their own personal development in the arts, but to sharing their skills and training generations of Bahamians who came after them.Four names come immediately to mind:

Sidney Poitier was not one of those individuals. Nor did he, like his fellow Bahamians in Hollywood, Calvin Lockhart and Cedric Scott, come home and give of his talent, expertise and skill to help develop those of us who were working in theatre in The Bahamas. There were times when we felt that he did not respect our continuing struggles, that he had shaken the Bahamian dust off his feet, and had turned his back on us altogether. The reason I understand the betrayal being expressed by many who are now working in the performing arts at the decision to establish something in his honour is that I too felt betrayed by him.And yet I support the idea that The Bahamas should honour him in some tangible, long-lasting fashion.I've thought about this long and hard, and have argued about it long and hard, long before this most recent controversy about Sidney Poitier's worthiness to be honoured. There was a time when I was like those people who opposed the awarding of honours to Sidney Poitier; what did he do for us? I wondered. What did he give to us? In meetings of the National Cultural Development Commission, when that body existed between 2002 and 2007, the same discussions that are being had in public in social media were held as we hammered out the National Heroes and Honours Bills; these questions were raised and discussed, with some of the members of that body, Bahamian icons in their own right, coming down on one side of the issue, some coming down on the other. (Both of those Bills were, to the best of my knowledge, presented in the House of Assembly in 2007 but which, for reasons presumably connected to the change of government in May of that year, are not functionally laws today. Perhaps they were not passed. Perhaps they were not ratified. No one seems to know.)I don't remember when or how my mind was changed; I don't think that it happened all at once. I do remember a moment, though, when, sitting in one of the symposia that accompanied the first Sidney Poitier Film Festival at the College of The Bahamas, I listened to an American academic who made a set of simple and clear points that I had never thought of before. Sidney Poitier changed the world for Black people in the 1950s. And he did it because he was from Cat Island. He did it because he was Bahamian.I don't feel the need to go through all the details that were given in that presentation. I'll just say it very simply. Until Poitier appeared on screen, the image of the black man that was circumnavigating the world was that of a shuffling, forelock-touching, yes-massa, servile sort of person, or else it was that of the cannibalistic savage dancing in a grass skirt around a fire, shaking a rattle and salivating at the thought of cooking up some prime white meat. There were some exceptions, like Paul Robeson in the 1936 film of Show Boat, but they were circumscribed by things that made them safe; Robeson's character Joe was, for all his strength and gravity, softened by the fact that he burst into song. Sidney Poitier didn't sing. He didn't take roles that made him out to be anything less than a man who deserved—and demanded—respect. Few black men, if any, spoke in Standard English on the silver screen. Poitier spoke English better than most Americans did. He looked into the camera, and dared you to call him "nigger" or "boy", and did it by using the dignity Cat Island instilled in him and not by inspiring fear.If that were all that Sidney Poitier did, I'd say that it would be appropriate for the land that raised him (and the land that he would also have been born in, if he hadn't arrived prematurely on that Miami trip) to honour him in some tangible and meaningful way. But I've learned that it wasn't all that he did. We tend to judge people's contributions to the nation by their notoriety, by their fame, and those people who simply do what they know to be right without looking for recognition seem to disappear into oblivion, while people who make a big fuss about their actions are placed on pedestals. Suffice to say that I'm convinced that Poitier has contributed, generously, to our nation through his support, financial and otherwise, of individual Bahamians.That said, I want to return to where I began—with reference to those people who mentored me in the performing arts. In all the discussion about why Poitier should or shouldn't be honoured and who should be honoured instead, I have not heard much mention of any of them. I wonder why. Like Poitier, they have all dedicated themselves to their craft, and have worked to make sure that whatever they produced was the best that they could possibly deliver. They didn't limit themselves by what they thought the Bahamian public would like or understand; instead, they pushed the envelope, tried different things, and inspired Bahamians to think differently about themselves, to dream better, to go further, to be better. They inspired me to do that. They taught the people they worked with to do it. They never thought that being Bahamian meant being second-rate at anything; the standard they upheld was universal and excellent. And yet their names are not called. Neither are the names of many others who worked, and work, according to the same criteria. I wonder why.So I am left, in all our discussion of respect for Bahamian artists, with the question of what it is we are respecting, and why. Is excellence one of our criteria? Is popularity? Is our discussion informed by a real appreciation for the work of all Bahamian artists, or only of those we know, recognize and support? Are we reasoning our way to our list of proposed honourees, or are we acting out of emotion? Are we seeking to rectify omissions of the past, or paving a pathway to the future?I don't know the answer to these questions. But I do know that now we have begun the discussion with Sidney Poitier we need to hold the discussion in earnest. And we have to hold it in the way I ask my students to write their papers—by establishing criteria and goals, by doing the research, by presenting the evidence, and by making our cases. And we have to do it as a nation, collectively, as a citizenry who know and articulate who and what it is we would like to be. By now it should be clear that we cannot leave it to others; we need to do it ourselves.

This morning, my heart and mind will be at Christ Church Cathedral, where my former minister and colleague, Charles Maynard, will be laid to rest. My body will not; I teach a class at the same time which I have not yet met and which meets once a week, and my first obligation is to them. But my heart and mind will be with Zelena, Charles' children, Mr and Mrs Maynard, Andrew, Nina, George, and the family at large.

Charles and I worked together for some eighteen months. He was the Minister of State for Culture; I was the Director of Cultural Affairs. Unlike his colleagues on both sides of the political divide, Charles got it. He was the first Minister of Culture to have had his own conscious, real investment in the business of culture, and he understood what we in The Bahamas needed in that regard. He and I didn't always agree, but he always allowed room for healthy discussion, and would always listen to dissenting views; even more strangely (for a politician), he would even allow himself to be convinced by another person's position if he felt that it had more merit than his own, or if he felt it could bear fruit. In other words, he made room, when I worked with him, for the possibility that he might be wrong. The rowdy persona that he adopted in the House of Assembly was miles away from the person he was in his ministerial office. There, he would join in a debate in his usual vigorous fashion, but as minister he would never ridicule you or dismiss your position outright. The typical malaise that we associate with Bahamian cabinet ministers, that of having instant expertise conferred upon them by God or the Governor when they take the oath of their office, did not afflict him; he had respect for the experts in the field and would bow to their expertise when necessary.

I loved and respected him as a minister. I knew that his desire was the same as ours—to develop Bahamian culture in such a way that it would become a beacon of pride for all citizens, an integral, perhaps a primary, part of the tourist package, and a source of income for many. He believed in us, in our worth, in our ability to create greatness. That he could not infect his colleagues with the same belief was not his fault; and so, like us, he deferred his dream.

He told me once, when we were in a passionate discussion about CARIFESTA and why we should hold it in The Bahamas at the time we had committed to do so (and he went to bat for us, all guns blazing, because he understood what it could do for a nation), that he was advised as a cabinet minister to make a choice. "Either you are a cultural activist, or you are a cabinet minister," he was told. "You need to pick a side." He was passing the choice on to me; "Either you are a cultural activist," he was saying, "or you are a civil servant." He made his choice. He believed, as almost all politicians do, that maintaining a position of power was the best way to effect the change that he wanted to see. I was not so sure about that; I knew which one I was. Our paths parted, and we continued working in the ways our consciences demanded. I am more committed than ever to make his dream real.

Perhaps coincidentally, today, August 24, is the day my father died, twenty-five years ago. For those who don't know, my father, E. Clement Bethel, was the first Director of Cultural Affairs in The Bahamas. He had the same dream that Charles and I shared, but he had it forty years before us. When the idea of the Bahamian nation was both embryonic and impossible, E. Clement Bethel was imagining greatness for Bahamian culture. In 2007, Charles Maynard was imagining the same. That we have not achieved it yet is not the fault of either man. The best legacy for Charles now is to honour him by making the dream a reality. I'm committed to it. Come join me.

And Charlie—rest in peace.

Hear, hear, Lynn. Love your womanish words.

Why is it so hard to find funding in this country for the Arts? And Im not talking about government funding here, or the tiny cheques we manage to beg from the odd supporter of our creative endeavors. Im talking about large gifts of financial support from the private citizens who dip into their multi-million dollar fortunes to create grants and foundations to support the development of the Arts in the communities where they live. Where, for example, is the Sir Stafford Sands Foundation for the Arts or the Tiger Finlayson Fund for the Literary Arts or the HG Christie Theatre for the Performing Arts or the Norman Solomon Arts Foundation? Where is the Rupert Roberts Endowment for the Arts, the Kelly Foundation, the Butler Foundation, the Lightbourn Fund for the Development of the Arts? Where are the libraries, museums and colleges the moneyed elite have created to nurture and enrich and give back to the communities that made them so wealthy to begin with?via Womanish Words.

Barbados has also taken an aggressive approach towards growing its creative economy and developing its creative class, implementing policies that take advantage of the CARIFROUM-EU Economic Partnership Agreement. This agreement allows Caribbean investment in European creative services and makes it easier to supply those services to the European market. In short, it provides easer market access and facilitates the formation strategic partnerships between Barbados and Europe for services from architecture to music. Barbados has also passed a Cultural Industries Development Bill which encourages private sector investment in the creative industries by using tax incentives for investments which support those industries.via Lessons from the East (and it’s not China) | tmg*.

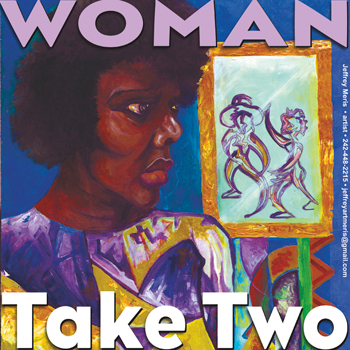

Yesterday, Arien Rolle, my former student and always friend, posted on Facebook that his mother, Telcine Turner-Rolle, Bahamian playwright, poet, storyteller, teacher and friend, had succumbed to the cancer she has been fighting for years.I cannot begin to express my sorrow at the news. I can't imagine a world without Telcine in it. I have known her, and of her, it seems all my life. She was my mother's friend and colleague in the early years of the College of The Bahamas. She was my colleague when I got my first adjunct appointment at the College to teach literature in 1986; she, like me, taught luminous young Bahamian intellectuals such as Ian Strachan and Tony Bethell—otherwise known by his professional intellectual name, Ian A. Bethell-Bennett. She alone, of Dr. Strachan's admiring teachers—he was an outstanding student, and his brain and his heart made him universally loved—dared to flunk him for not doing his work, which meant that, he couldn't give the valedictorian speech he had planned to give at graduation. He challenged the grade; she won. She was uncompromising, unrelenting, a hard taskmaster, not content to let talent languish untrained or untested. I am sure she pushed Ian because she knew just how brilliant he was, and she was not afraid to do so. She frightened me.Later, when I took over teaching full time, I had the pleasure of teaching Telcine's only child and son Arien in a class of people almost as brilliant as the first class I ever taught, which was at COB when I met Ian and Tony for the first time. Meeting Telcine the mother was an entirely new experience. Telcine the uncompromising, the brilliant, the prize-winning playwright, regarded Arien as her greatest work, and he was a work in progress. She raised him as she saw fit—which didn't necessarily mesh with what anyone else thought, not even the redoubtable Sammie Bethell at St. Anne's. When Telcine judged Arien was not well enough to go to school, she kept him home, and would send him later with expertly written notes on memorable paper—tinted sometimes, scented sometimes, always incontestable. Arien, for his part, was the most well-balanced, self-contained, even-tempered student I had yet met, who tolerated his mother's attentions without ever complaining.I knew and worked with Telcine's husband and widower, James. He had worked with my father before me, and had charge of the art that went through the Cultural Affairs Division, and was in charge of Jumbey Village before its destruction in the late 1980s. He was one of the senior civil servants who took over as acting Director of Cultural Affairs in the seven years that passed between my father's death and the appointment of Cleophas Adderley to that post. He, like Telcine, invested his own brand of excellence into Arien, and he also invested himself into Telcine, who was always uncompromising and often considered "difficult".There is a reason that her masterpiece, Woman Take Two, was not performed for many years after it won the Commonwealth Prize for literature. This was because she was as uncompromising about its direction as she had been about writing it. She should have directed the play herself; but she wanted it handled by someone else. Not until 1994, when David Burrows began his local directing career, did she find someone who would be as accommodating of her views of the play as he was enthusiastic about the play itself, and so it was David Burrows—David Jonathan, as Telcine insisted on calling him—who had the honour of staging Woman Take Two for the first time, almost twenty years after it was written. The bond he developed with Telcine lasted for the rest of her life, as she was as loyal to her friends and allies as she was uncompromising, unconventional, and perfectionist.I think that as I write this, I am expressing the deep admiration, and, I admit it, the little bit of fear, that I had for and of Telcine. I respected her craft, which was as rigourous as her talent was great. In our country, where talented people often simply let their talent run wild, Telcine was a hard taskmaster. I got the sense that she let nothing leave her desk until she was completely finished with it. She had a mind like a razor, and if she ever offered criticism you'd better take it and follow it. She was one of our greatest playwrights, and one of our best known and beloved. She was an unconventional mother, but a successful one; her son Arien is a gentleman and a scholar. I happen to agree with Telcine that he has not yet achieved his full potential—he is a young man who is brimming over with talent—but he is her greatest work.This week I grieve with Arien and James, and with the rest of the cultural community of The Bahamas. We have lost one of our greatest stars. May Telcine Turner-Rolle rest in peace, and may we honour her lifelong commitment to excellence with excellence of our own.

Yesterday, Arien Rolle, my former student and always friend, posted on Facebook that his mother, Telcine Turner-Rolle, Bahamian playwright, poet, storyteller, teacher and friend, had succumbed to the cancer she has been fighting for years.I cannot begin to express my sorrow at the news. I can't imagine a world without Telcine in it. I have known her, and of her, it seems all my life. She was my mother's friend and colleague in the early years of the College of The Bahamas. She was my colleague when I got my first adjunct appointment at the College to teach literature in 1986; she, like me, taught luminous young Bahamian intellectuals such as Ian Strachan and Tony Bethell—otherwise known by his professional intellectual name, Ian A. Bethell-Bennett. She alone, of Dr. Strachan's admiring teachers—he was an outstanding student, and his brain and his heart made him universally loved—dared to flunk him for not doing his work, which meant that, he couldn't give the valedictorian speech he had planned to give at graduation. He challenged the grade; she won. She was uncompromising, unrelenting, a hard taskmaster, not content to let talent languish untrained or untested. I am sure she pushed Ian because she knew just how brilliant he was, and she was not afraid to do so. She frightened me.Later, when I took over teaching full time, I had the pleasure of teaching Telcine's only child and son Arien in a class of people almost as brilliant as the first class I ever taught, which was at COB when I met Ian and Tony for the first time. Meeting Telcine the mother was an entirely new experience. Telcine the uncompromising, the brilliant, the prize-winning playwright, regarded Arien as her greatest work, and he was a work in progress. She raised him as she saw fit—which didn't necessarily mesh with what anyone else thought, not even the redoubtable Sammie Bethell at St. Anne's. When Telcine judged Arien was not well enough to go to school, she kept him home, and would send him later with expertly written notes on memorable paper—tinted sometimes, scented sometimes, always incontestable. Arien, for his part, was the most well-balanced, self-contained, even-tempered student I had yet met, who tolerated his mother's attentions without ever complaining.I knew and worked with Telcine's husband and widower, James. He had worked with my father before me, and had charge of the art that went through the Cultural Affairs Division, and was in charge of Jumbey Village before its destruction in the late 1980s. He was one of the senior civil servants who took over as acting Director of Cultural Affairs in the seven years that passed between my father's death and the appointment of Cleophas Adderley to that post. He, like Telcine, invested his own brand of excellence into Arien, and he also invested himself into Telcine, who was always uncompromising and often considered "difficult".There is a reason that her masterpiece, Woman Take Two, was not performed for many years after it won the Commonwealth Prize for literature. This was because she was as uncompromising about its direction as she had been about writing it. She should have directed the play herself; but she wanted it handled by someone else. Not until 1994, when David Burrows began his local directing career, did she find someone who would be as accommodating of her views of the play as he was enthusiastic about the play itself, and so it was David Burrows—David Jonathan, as Telcine insisted on calling him—who had the honour of staging Woman Take Two for the first time, almost twenty years after it was written. The bond he developed with Telcine lasted for the rest of her life, as she was as loyal to her friends and allies as she was uncompromising, unconventional, and perfectionist.I think that as I write this, I am expressing the deep admiration, and, I admit it, the little bit of fear, that I had for and of Telcine. I respected her craft, which was as rigourous as her talent was great. In our country, where talented people often simply let their talent run wild, Telcine was a hard taskmaster. I got the sense that she let nothing leave her desk until she was completely finished with it. She had a mind like a razor, and if she ever offered criticism you'd better take it and follow it. She was one of our greatest playwrights, and one of our best known and beloved. She was an unconventional mother, but a successful one; her son Arien is a gentleman and a scholar. I happen to agree with Telcine that he has not yet achieved his full potential—he is a young man who is brimming over with talent—but he is her greatest work.This week I grieve with Arien and James, and with the rest of the cultural community of The Bahamas. We have lost one of our greatest stars. May Telcine Turner-Rolle rest in peace, and may we honour her lifelong commitment to excellence with excellence of our own.

Check this out:

Nassau, What Happened? Is a group project that anyone can contribute to by adding his or her own line to a collective poem about the city of Nassau. It will be part of Transforming Spaces 2012 under the theme of “Fibre”.Inspired by an exercise by the poetry festival O, Miami, this exercise is designed to bring many voices together at once in order to hint at a larger, complex voice.via Nassau, What Happened?.

Got a piece of terribly bad news this morning: the Zybines are dead. They were found in their Mexico home, having both succumbed to carbon monoxide poisoning from their heater.For those people who don't know, Alex and Violette Zybine were dancers who worked in The Bahamas during the 1960s and 1970s. They were engaged by Hubert Farrington to look after the fledgling Nassau Civic Ballet while he worked at the Metropolitan Opera in New York -- in fact, that's where he met Alex. Violette was my first, and only, ballet teacher. Alex founded the New Breed Dancers and most of the successful Bahamian classical dancers of that era were trained by him -- among them Lawrence Carroll, Christine Johnson, Paula Knowles, Ednol Wright, and Victoria McIntosh, among others. They returned to Nassau four or five years ago, and were planning another visit. I heard from Violette, as I always do, just after Christmas, with a set of lovely photographs. I'll share just two of them here. May they rest in peace.

We Bahamians are considered such philistines around the region. They laugh at us for stooping so low as to blow up our own culture, and that's not a joke - it actually happened in 1987, when the government demolished Jumbey Village with explosives.The village was an offshoot of a community festival launched in 1969 by musician and parliamentarian Ed Moxey. An earlier and more 'cultural' version of the fish fry, it featured music and dance performances as well as displays of arts and crafts, and local produce, and was aimed at locals as well as tourists.In 1971 Moxey persuaded the Pindling government to let the festival take over a former dump site on Blue Hill Road and build a permanent facility. In the period leading up to independence in 1973, there was a lot of buzz about a popular enterprise promoting Bahamian creative arts."We put the homestead site up and in '73 we had a meeting with all the teachers. And they agreed right there that all the teachers in the system would donate a half day's pay and every school would have a function...and we came up with $100,000 in the space of three months," Moxey recalled."We put up a special cabinet paper, cabinet agreed, and when I pick up the budget, everything was cut out. Everything." Moxey told University of Pennsylvania researcher Tim Rommen in 2007. "That was a little bit too much. Village lingered, lingered...just kept on deteriorating until they came up with this grandiose scheme to put National Insurance there. And when they ready, they blow the whole thing down."via Bahama Pundit.

With the curtain call of Julius Caesar, at 10:30 tonight, the 2011 Shakespeare in Paradise theatre festival officially came to an end.We would like to thank all of our performers, directors, volunteers, staff, guests artists, sponsors and of course our audiences who helped to make this year’s festival a success.For the majority of us, this festival is a labour of love as we try to keep theatre alive in our country and give a number of young people the opportunity to do more constructive things with their lives.Your continued support of our festival is most appreciated and we look forward to that support in our 4th annual theatre festival in 2012.via Shakespeare in Paradise — A Theatre Festival for Nassau and the World.

It's a new century. It's the age of culture.When are we going to be joining it?YouTube - Il Volo - EPK.This is the kind of opportunity you are letting your citizens miss. With vision, boys like Osano Neely and Matthew Walker could have done this. Without vision and support, all we can do is bend over and take foreign investment in places where the sun don't shine.Am I angry?You bet.Always.

Ward Minnis' new play, The Cabinet, is a popular success. It's got a sure-fire premise, being a cynical look at party politics. Never mind that the action is set in the fictional "Archipelago Islands", featuring the leaders of the Peas N Rice (PNR) party and the Flamingos; the audience all know Minnis is talking about The Bahamas. Moreover, he's providing us with a thinly disguised take on the recent general elections in 2002 and 2007, with the Flamingos' fall from power (carefully engineered by Reginald Moxey, their leader, played by Chigozie Ijeoma) and the ascension of the PNR, led by Jerome Cartwright (Ward Minnis), and then Moxey's return to power thereafter.It's got a ghost for good measure, and it doesn't hurt that it's of a dead Prime Minister—the late Sir Lymon Leadah (Ian Strachan). It's got a sweet but ineffectual stand-in for power, Kendrick Johnson (played by Matthew Wildgoose), a conniving and manipulative female sidekick, Latoya Darling, M.P., played by Sophie Smith, and a defeated second-in-command, Fenton Green (Arthur Maycock). It's got laughs. It's got some seriously clever moments. It's got a solid premise—that the ghost of Sir Lymon Leadah helps to engineer a dastardly plan to allow Reggie Moxey to "keep his word and break it at the same time". It's got conflict. It's got characters, and it's solidly acted to boot. It's a play, and a funny one at that.But.When I go to the theatre, I want to be entertained, yes, but I want to be captivated too. I want to be removed from my everyday life by more than the darkness of the theatre; I want to be told a story that surprises and delights (or appals, if it's that kind of play). I want to enter a different world.And this is where The Cabinet fell short for me. The story was just too familiar. Now I may be in the minority here, but if I'm going to spend two hours and twenty minutes at a live production, it'd better deliver a little more than just laughs. I'm looking for a story that tells me something new; I'm looking for a play that goes beyond naked predictability.To be fair, the first five scenes of The Cabinet promised something more. These are the scenes in which the dramatic tension is building, and even though the story is familiar, the spin placed on it is fresh enough to intrigue. Lymon Leadah's ghostly appearance to a drunken Reginald Moxey makes for a strong beginning, and the vulnerability of Moxey at that moment is a strong way to start a tale about an almost-dictator and his machinations. As those machinations unfold, moreover, and Moxey attempts to propose his plan to the bumbling Kendrick, the tension builds; for Kendrick isn't as much of a pushover as Moxey expects, and Matthew Wildgoose's Kendrick reveals a self-deprecating integrity that inspires a sliver of respect along with our laughter at his muddles. To this point, the Archipelago Islands are not The Bahamas, and we are willing to accept that different things might happen there.Jerome Cartwright, Kendrick Johnson and others may be inspired by real people in our political past, but Matthew Wildgoose and Ian Strachan in particular make it clear in their protrayals that they are not actually pretending to be Tommy Turnquest or Lynden Pindling onstage. What lets the play down is the character of Reggie Moxey, who can be nothing but Hubert Alexander Ingraham in disguise; Ijeoma's playing of it, which consists of an extremely clever impersonation throughout, leaves no doubt. And thus the damage is done. Instead of leading the audience to invest in a story that may parallel our own but has enough twists in it that we are pushed beyond the everyday, the play simply goes over well-trodden ground.After the opening, then, it is too easy to let one's focus slip. If one knows recent Bahamian history, there's no tension at all. There's no subtext, there's no suspense. The only reason to remain sitting in the audience is to see what gems the writer and the actors will deliver next.And this is a shame, because although there are gems throughout—such as when Cartwright, the Leader of the Opposition/then Prime Minister/then Leader of the Opposition, waxes eloquently off into neverland ("I have consulted extensively and attenuated bureaucracy"), or when Moxey delivers lines that are well known from other, more famous contexts, such as "I have heard the voice of the people. Who am I to argue with the will of the people?"—the writing alone cannot sustain one's full attention. What happens instead is that the actors—Ijeoma in particular, but Minnis himself at times—take refuge in the easy laugh to bring the audience back on board.There are issues with the production as well. Some of these may come down to the script itself, which starts well but loses its way in the middle, and never quite recovers its equilibrium thereafter. After the set-up, the dramatic tension lags as the result of too many small scenes going nowhere fast. This could have been addressed both by judicious trimming of fat that didn't move the story along, and by intercutting one scene with another to pick up the pace and add layers of activity. The real question, it seems to me, is how Reggie Moxey is going to pull off the sleight of hand that enables him to run for more than two terms while at the same time gaining the trust of the citizenry; the main conflict, as written, is between Leadah and Moxey in a game of political wits. The play would have been made even stronger if Moxey's adversaries were not so one-dimensional, if there seemed to be some doubt, even though the audience "knows" the story, that he would succeed. Instead, we appear to have to take it for granted that because Ingraham always gets his own way, Moxey must as well.Other issues come down to technical choices. There's no real need, for instance, for there to be a blackout after every single scene, especially when there are three playing areas onstage; actors can simply cross from one location to another without losing momentum. Such a strategy would also have eliminated the need to find so much scene-change music, much of which seemed to have very little to do with the story at hand.More thought could certainly have been given to the layout of the stage, which had Reggie Moxey's dining table centre stage, necessitating its movement upstage and downstage to keep it from blocking the other playing areas. Given that there are two political parties represented, and two political leaders, it would have made perfect sense to have set the leaders' homes stage right and stage left, leaving centre stage as the Prime Minister's office; a simple platform would have elevated that office and resolved sight issues all at once.Those who attended The Cabinet over the last two weekends and enjoyed it may find these criticisms picky, even petty. They are necessary, though, because the play itself has so much going for it. It's got the story, it's got the characters, and it's got the timing to make it succeed for the moment. But what it should be looking to do is to last, to be able to be revived, not at the end of the month, but in five or ten years' time, and produced by a different cast doing different things. This is, after all, a play, something that has characters in conflict with one another working to achieve catharsis in its audience. And I'm afraid that under those circumstances it's not enough to write a play that inspires us just to laugh. What is required is the production of a funny work that also gets us to think.

To three Caribbean artists who passed recently: SAMANTHA PIERRE, Trinidadian storyteller, ARROW the super Soca Man from Montserrat. NEIL ISAACS, part of the Guyana theatre scene.[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nLzkDDE9TkQ&fs=1&hl=en_US]